Performance of Yeomillak (“Joy of the People”) court music composed during the reign of King Sejong in the 15th century

Gugak

The term gugak, which literally means “national music,” refers to traditional Korean music and other related art forms including songs, dances, and ceremonial movements. The history of music in Korea should be as long as Korean history itself, but it was only in the early 15th century, during the reign of King Sejong of the Joseon dynasty (1392–1910), that Korean music became a subject of serious study and was developed into a system, resulting in the creation of the first mensural notation system called jeongganbo in Asia. King Sejong’s efforts to reform the court music led not only to the creation of Korea’s own notation system but also to the composition of special ritual music called Jongmyo Jeryeak to be performed during the royal ancestral ritual (Jongmyo Jerye) in the Jongmyo— inscribed on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2001—and Yeomillak, or “Joy of the People.” The term gugak was first used by the Jangagwon, a government agency of late Joseon responsible for music, to distinguish traditional Korean music from foreign music.

Traditional Korean music is typically classified into several types: the “legitimate music” (called jeongak or jeongga) enjoyed by the royalty and aristocracy of Joseon; folk music including pansori, sanjo, and japga; jeongjae (court music and dance) performed for the King at celebratory state events; music and dance connected with shamanic and Buddhist traditions such as salpuri, seungmu, and beompae; and poetic songs beloved of the literati elite such as gagok and sijo. Of the numerous folk songs, Arirang—inscribed on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2012—is particularly cherished by the common people and there exist many variations with special lyrics and melodies unique to each region such as Miryang, Jeongseon, and Jindo.

Gugak instruments are similarly diverse. These traditional musical instruments are generally divided into three categories: wind instruments such as the piri, daegeum, danso, and taepyeongso; stringed instruments such as the gayageum, geomungo, haegeum, ajaeng, and bipa; and percussion instruments such as the buk, janggu, pyeonjong, pyeongyeong, kkwaenggwari, and jing.

Buchaechum (Fan Dance)

A traditional form of Korean dance usually performed by groups of female dancers

Folk Dance

Korean people have inherited a great variety of folk dances such as salpurichum (spiritual purification dance), gutchum (shamanic ritual dance), taepyeongmu (dance of peace), hallyangchum (idler’s dance), buchaechum (fan dance), geommu (sword dance), and seungmu (monk’s dance). Of these, talchum (mask dance) and pungmul nori (play with musical instruments) are known for their satirical targeting of the corrupt aristocracy of Joseon and their close connection with rural communities, which had long been the bedrock of Korean culture and tradition. Most performances are presented in a marketplace or on the fields and involve drumming, dancing, and singing, all of which are used to create a highly elated atmosphere.

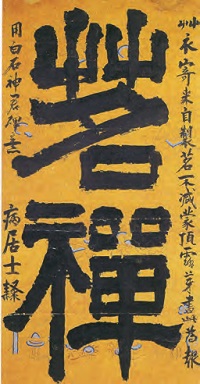

“Myeong-Seon (Meditation with Tea)” by Kim Jeong-hui (pen-name: Chusa, 1786–1856) (Joseon, 19th century)

Painting and Calligraphy

Painting has always been a major genre of Korean art since ancient times. The art of ancient Korea is represented by the tomb murals of Goguryeo (37 BCE– 668), which contain valuable clues to the beliefs of the early Korean people about humanity and the universe, as well as to their artistic sensibilities and techniques. Their art had been influenced by China and disseminated to Japan. The artists of Goryeo (918–1392) were interested in capturing Buddhist icons and bequeathed some great masterpieces, while the literati elite of Joseon was more attracted not only to idealized landscapes but also to the symbolism of plants and animals, such as the Four Noble Lords (Sagunja, namely, the orchid, chrysanthemum, bamboo, and plum tree) and the Ten Creatures of Longevity (Sipjangsaeng), including crane, tigers, and deer.

Korea in the 18th century saw the arrival of two great artists, Kim Hong-do and Sin Yun-bok, both of whom developed a passionate interest in depicting the daily activities of ordinary people in their work. Kim Hong-do preferred depicting the kaleidoscope of people in various situations and scenes of everyday life, whereas Sin Yun-bok, for his part, devoted his efforts to capturing erotic moments in works that were surprisingly voyeuristic for the period.

Calligraphy, which developed in Korea under the influence of China, is the art of handwriting in which the beauty of the lines and forms of characters and the energy contained in brush strokes and subtle shades of ink are appreciated. While calligraphy is an independent genre of art, it has been closely related to ink and wash painting because these forms use similar techniques and the tools commonly called the “Four Treasures of the Study” (i.e., paper, brush, ink stick, and inkstone). Korea has produced an abundance of master calligraphers, of whom Kim Jeong-hui (1786–1856) is particularly famous for developing his own style known as Chusache or Chusa Style (Chusa was his pen name). His calligraphic works are still widely admired for their remarkably modern artistic beauty.

“Ssireum (Korean wrestling)” by Kim Hong-do (pen-name: Danwon, 1745–1806) (Joseon, 18th century)

This genre painting by Kim Hong-do, one of the greatest painters of the late Joseon period, vividly captures a scene of traditional Korean wrestling where two competing wrestlers are surrounded by engrossed spectators.

Pottery

Kiln Site in Gangjin, Jeollanam-do

The remains of ancient kilns can be seen in Gangjin, the largest production site of celadon during the Goryeo period.

Korean pottery, which nowadays attracts the highest praise from international collectors, is typically divided into three groups: Cheongja (blue-green celadon), Buncheong (slip-coated stoneware), and Baekja (white porcelain). Celadon refers to Korean stoneware, which underwent major development in the hands of Goryeo potters some 700 to 1,000 years ago. Celadon pottery is marked by an attractive jade blue surface and the unique Korean inlay technique used to decorate it. Gangjin of Jeollanam-do and Buan of Jeollabuk-do were the two main producers during the Goryeo period (918–1392).

1. Celadon Melon-Shaped Bottle (Goryeo, 12th century)

2. Celadon Jar with Peony Design (Goryeo, 12th century)

3. Buncheong Bottle with Lotus and Vine Design (Joseon, 15th century)

4. White Porcelain Bottle with String Design in Underglaze Iron (Joseon, 16th century)

100 to 600 years ago, white porcelain ware was the main representation of Korean ceramic art. While some of these porcelain wares display a milky white surface, many are decorated with a great variety of designs painted in oxidized iron, copper, or the priceless cobalt blue pigment imported from Persia via China. The Royal Court of Joseon ran its own kilns in Gwangju, Gyeonggi-do, producing products of the highest quality. The advanced techniques used in the production of white porcelain wares were introduced to Japan by Joseon potters kidnapped during the Imjin Waeran (Japanese invasion of Korea 1592–1598).

The third main group of Korean pottery is Buncheong ware, which was independently made by Goryeo potters 500 to 600 years ago after the fall of their Kingdom.

Today, traditional artworks such as paintings, calligraphy works, and pottery are widely traded through auctions in galleries and antique shops in Insa-dong, Seoul.

Handicrafts

In the past, Korean craftsmen and women developed a wide range of techniques to produce the items they needed at home. They made pieces of wooden furniture such as wardrobes, cabinets, and tables marked by a keen eye for balance and symmetry, and wove beautiful baskets, boxes, and mats with bamboo, wisteria, or lespedeza. They used Korean mulberry paper to make masks, dolls, and ceremonial ornaments, and decorated diverse household objects with black and red lacquer harvested from nature to make them stronger and more beautiful.

Later, they developed the art of using beautifully dyed ox-horn strips, and iridescent mother-of-pearl and abalone shell to decorate furniture. Embroidery, decorative knot making (maedeup), and natural dyeing were also important elements of traditional Korean arts and crafts, which were widely exploited by women to make attractive garments, household objects, and personal fashion ornaments.

Two-Tier Chest

This durable and practical wooden chest used for storing clothes is lavishly decorated with a mother-of-pearl inlay design.

Women’s toiletry cases

Naturally dyed fabrics with different colors

Norigae/maedeup (knots of norigae) and other embroidered accessories

Korean mulberry paper dolls made of hanji is Korean traditional handmade paper